What good learning experience design looks like

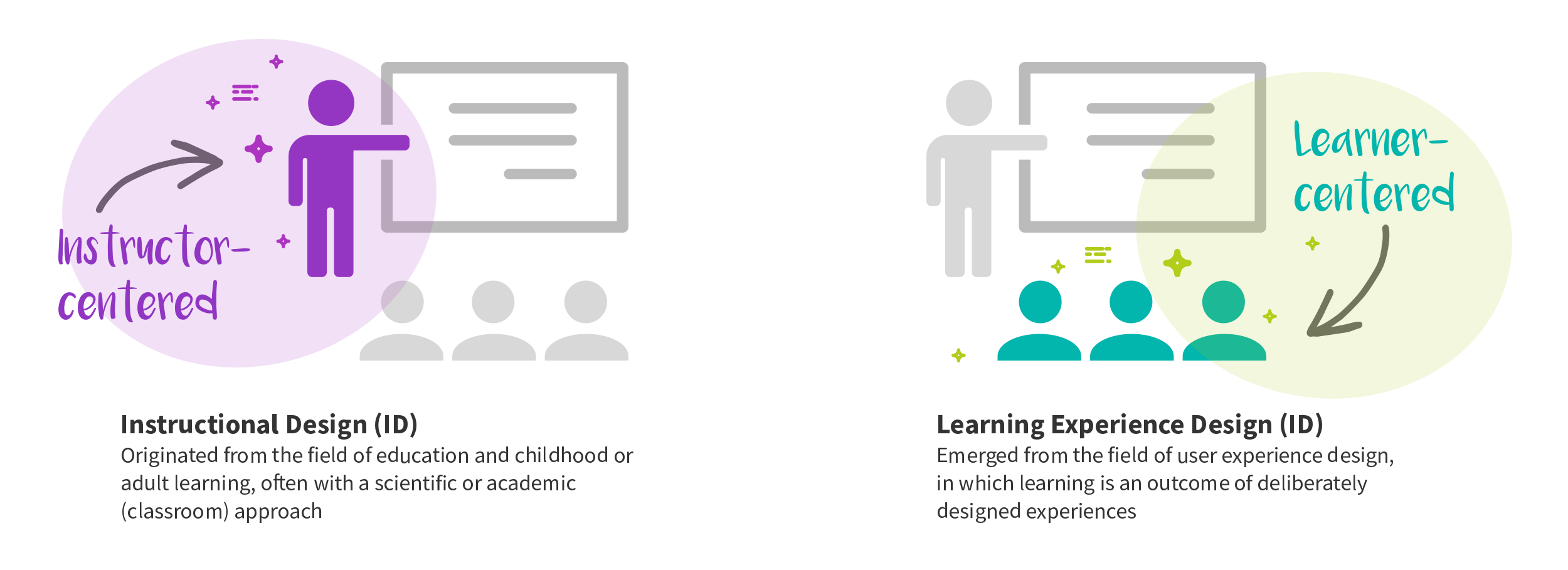

How is Learning Experience Design different from Instructional Design?

The distinction between Instructional Design (ID) and Learning Experience Design (LXD) parallels the difference between a traditional business or product launch—which was business-centric—compared to how human-centered design puts the focus on end users, stakeholders, and larger systems dynamics first, THEN ensuring the business processes support the desired user goals … rather than expecting customers to adapt themselves to the requirements of the business.

Design each learning experience with clear objectives resulting in outcomes the learner recognizes as accomplishing their goal.

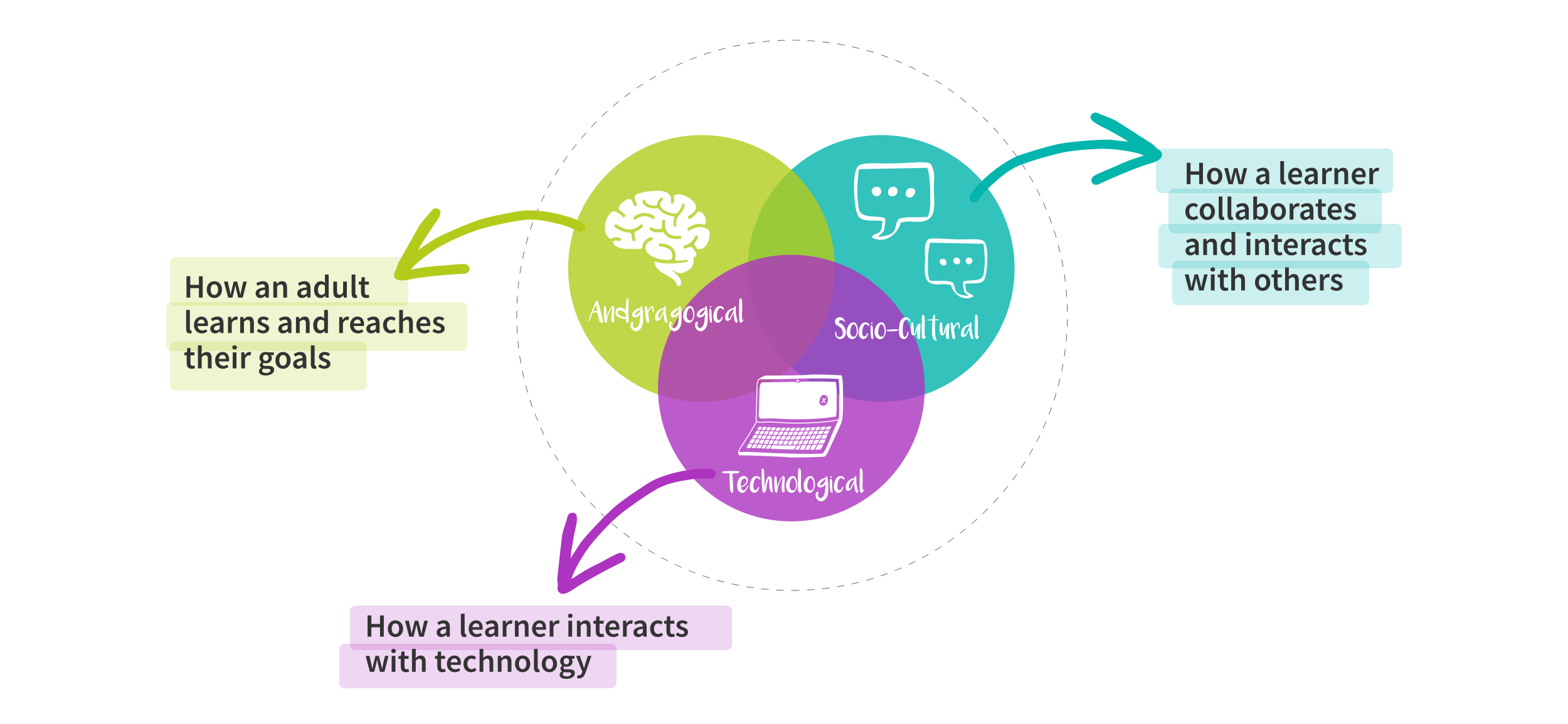

We learn from the fullness of our lived experience, not just from consuming content pushed at us. Our learning outcomes are influenced by how our brains create new connections, make decisions, and reflect on the results; our interactions with other learners and people in the environment; and how technology assists or holds us back.

Adapted from image by Aletheia Délivré.

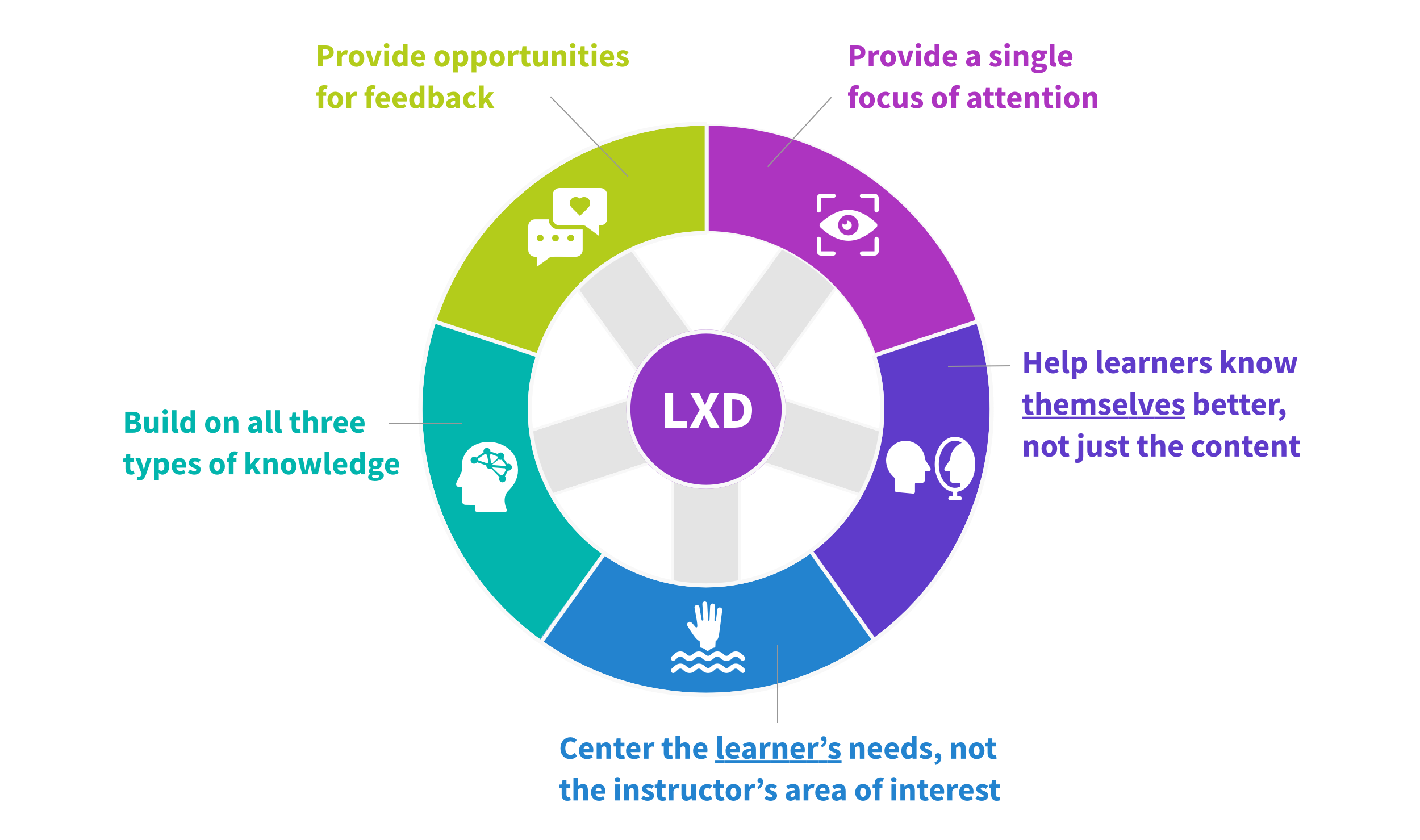

Principles of LXD

Provide a single focus of attention

Keep each module and activity focused on one outcome. Additional details or variations may be fascinating to an expert, but can be bewildering and discouraging to the novice. Don’t try to “cover” everything all at once.

Help learners know themselves better, not just the content

Provide time for learners to:

Test themselves to identify remaining gaps in knowledge

Reflect on what learning strategies worked and why

Consider the relevance of what they’re learning to their real life

Center the learner’s needs, not the instructor’s area of interest

Establish what the learner already knows

Design tasks to be gradually more cognitively demanding

Let learners make meaningful connections, don’t just give all the answers

Build on all three types of knowledge

Declarative knowledge (what to do)

Procedural knowledge (how to do something). Combine procedural knowledge with declarative knowledge to help learners develop complex skills

Experiential learning (learning by doing). Giving learners a chance to work with concepts is ideal for complex skills, building in space repetition and deliberate practice for reinforcement (e.g., practice scenarios, assignments, challenge prompts, etc.)

Provide opportunities for feedback

Feedback is a rich technique to further shape and develop what the learner knows. Three key types to provide:

Instructor feedback

Peer feedback

Assignment responses

Adapted from Learn Jam What makes an effective learning experience?

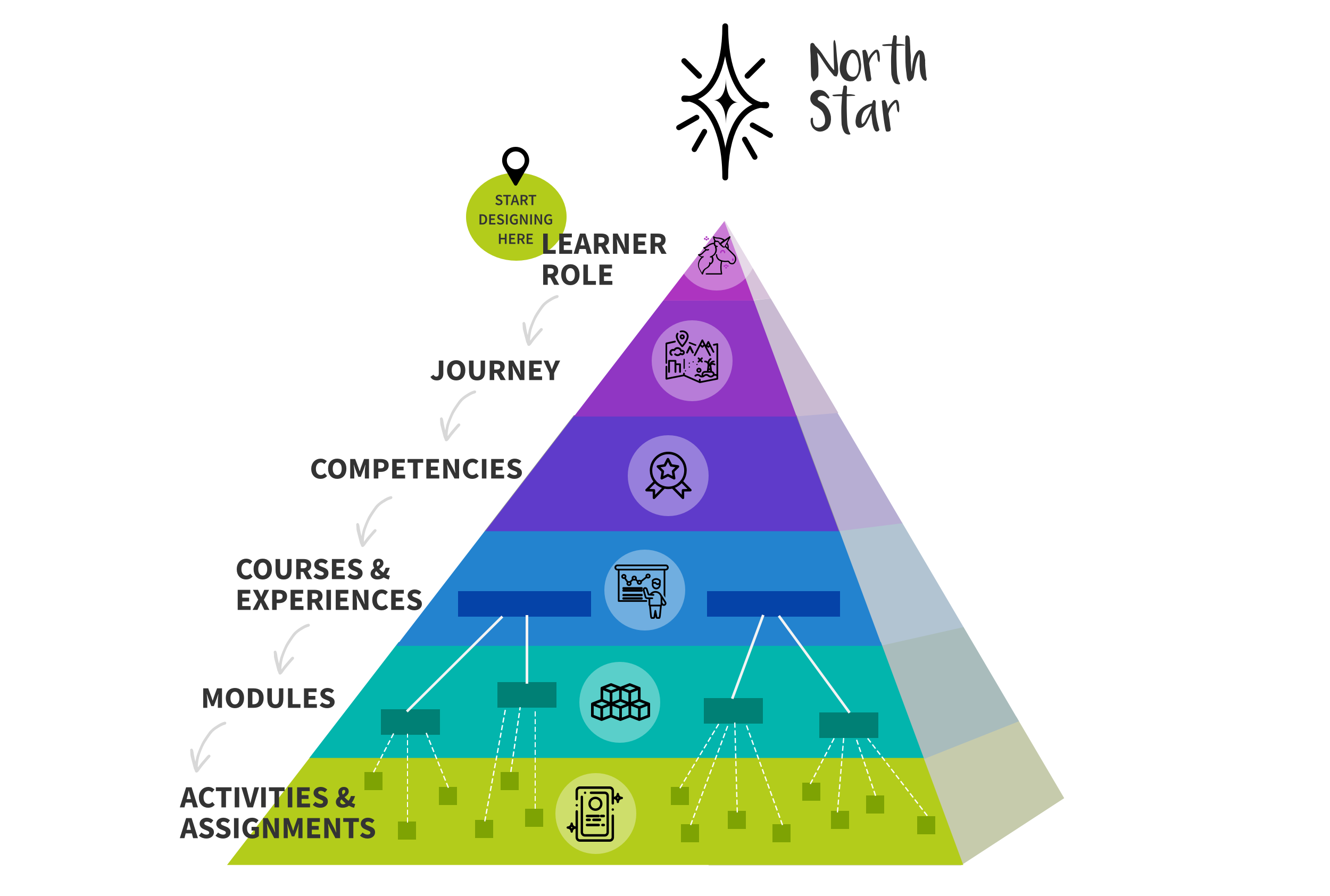

Model for planning new courses

In a learner-centered approach, begin planning courses by considering who the learner is, what they want to accomplish, and how they would like to grow. From there, progressively work through what it will take to help them achieve that, ending the process with the specific activities and content they’ll need.

It’s tempting to start with the content and activities that are most familiar to the instructor and build up from there, but that risks missing the needs and current understanding of the learner.

Planning Pyramid by Kimberly Zahler

Process for creating new courses

In each stage of the process, the course concept becomes more refined. However, it should not be misinterpreted to think that it is a straight march from topic to content creation. As with all design, the final product will be stronger by using an iterative process, gathering feedback along the way.

A truly human-centered approach will start with insights gleaned from talking with actual learners and gather feedback on prototypes before investing heavily in production.

Topic Selection

Select the topic for the course(s).

Main Question: What is the purpose of this course or experience?

Target Learners

Identify the target learner profile(s). Zoom in on the problem the learner wants to solve, and where they are in their journey. Consider what they already know and what their context is.

Main Questions: Who are the target learners? What they want to do, learn, or overcome? How will they be better off at the end of this course? How will they be closer to their transformation goal?

Objectives & Outcomes

Define what the learning experience will achieve for learners and the business

List the observable outcomes (results and behaviors) during and after the learning experience

Map to your competency model (if using)

Draft the course promise

Main Questions: As a result of this course, what will learners be able to do differently that they couldn’t do before? What are the learner’s pain points? How will this course provide value?

Experience Design

Break the topic into modules with an objective for each

Select (or create) activities that will result in the desired outcomes for the learners. Match the style and “altitude” or information to the learner profile—do they need an overview and general direction, a chance to practice, or a detailed step-by-step introduction?

Orchestrate a “rhythm” of activities, alternating between lecture, individual, and group activities

Main Questions: What methods or activities will help learners achieve their goals after the course (learner skill)? In what ways will leaners best acquire this new skill (teaching modality)? Is the experience feasible and sustainable for the training team to deliver? What alternatives might we consider to deliver the same value to leaners while reducing the burden for the training team?

Content Creation

Design the slide deck, worksheets, videos, downloads, whiteboards, and other assets to bring the course to life!

A course promise is a marketing tool to describe the value of the course and why learners should enroll. The promise made to learners before they purchase should match the experience they have in the course.

Starting Points

✅ Where to start

Important, enduring ideas that are worth understanding (e.g., “Models enable us to test possible outcomes or effects”)

Topics with essential questions that must be continually revisited (e.g., Whose “history” is this? How precise do I have to be? How does culture shape art and vice versa?)

A powerful process or strategy for using many important skills (e.g., Conducting a scientific inquiry)

An inquiry into complex issues or problems (e.g., Research into employee culture change)

❌ Where not to start

A favorite learning activity (e.g., Making a model volcano with baking soda and vinegar)

Questions with factual answers (e.g., What is the chemical symbol for iron? What is alliteration? How do you add fractions?)

A single important process (e.g., Using a microscope)

A basic skill that requires only drill and practice (e.g., Keyboarding)

Adapted from The Understanding by Design Guide to Creating High-Quality Units by Grant Wiggins and Jay McTighe, ASCD (2011).